The Littoral Combat Ship did not have a smooth birth. Initially conceived as a sort of coastal corvette, it was adopted by Donald Rumsfeld in his attempt to transform how the US military did business, and soon morphed into a quite large and very fast ship that was supposed to carry modular systems to allow it to fulfill a variety of missions in dangerous coastal waters. Cost overruns drew Congressional ire, but the program survived, and 35 ships are either in service or under contract.

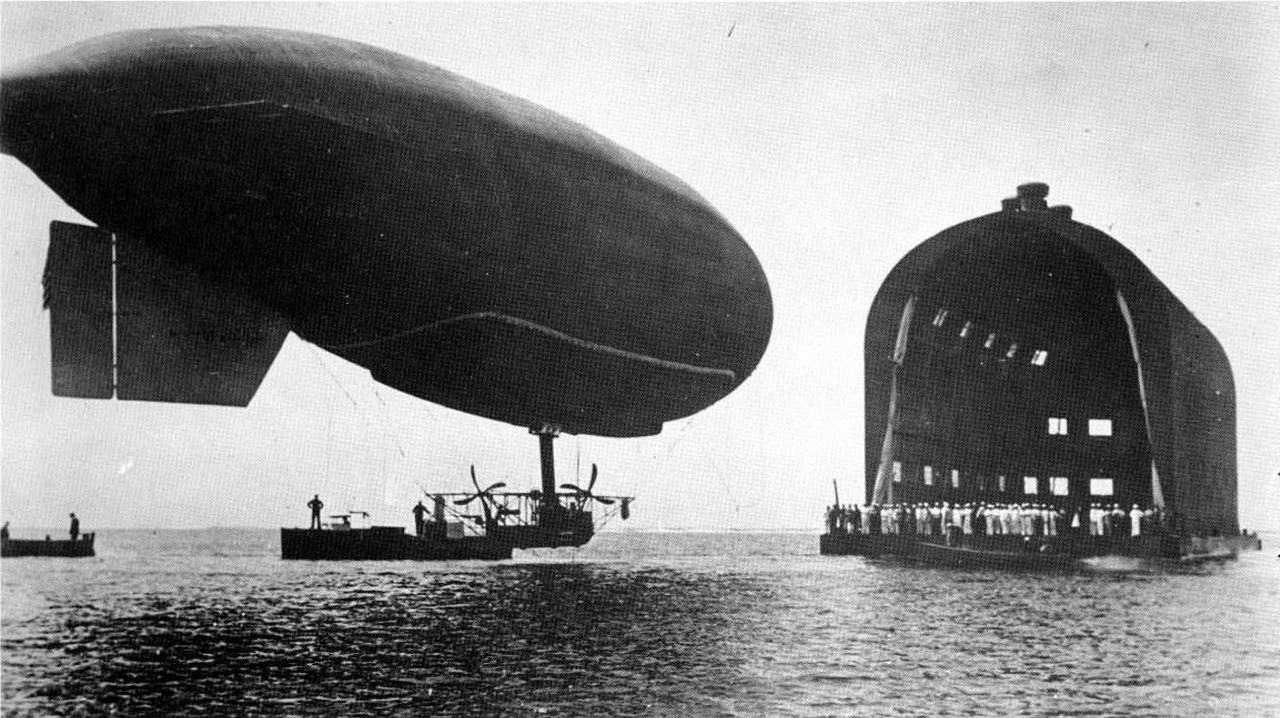

An unmanned MQ-8B Fire Scout comes in to land aboard Coronado (Independence class)

But what sort of ships are they? Two different variants have been procured, the LCS-1/Freedom class, built by Lockheed Martin and Marinette Marine in Marinette, Wisconsin, and the LCS-2/Independence class built by Austal USA at their yard in Mobile, Alabama.1 Despite being built to the same specifications, they are radically different designs. The Lockheed ship is a semi-planing monohull made of steel, while Austal's is a striking aluminum trimaran, both forms driven by the requirement for a speed of around 45 kts, which isn't really practical with a conventional hull.2 Read more...

Recent Comments