Greyhound is a movie I really wanted to see in theaters, but didn't get a chance to. Apple picked it up for their streaming service, which really annoyed me, because if it had done well in theaters, it might have inspired some immitators.

On the whole, I liked the movie. This was clearly done by someone who had a better appreciation for the atmosphere of the actions they were portraying than did, say, the people behind Midway, and it stays reasonably true to the book. But I watched it at my computer instead of on the big screen, and that led to some problems.

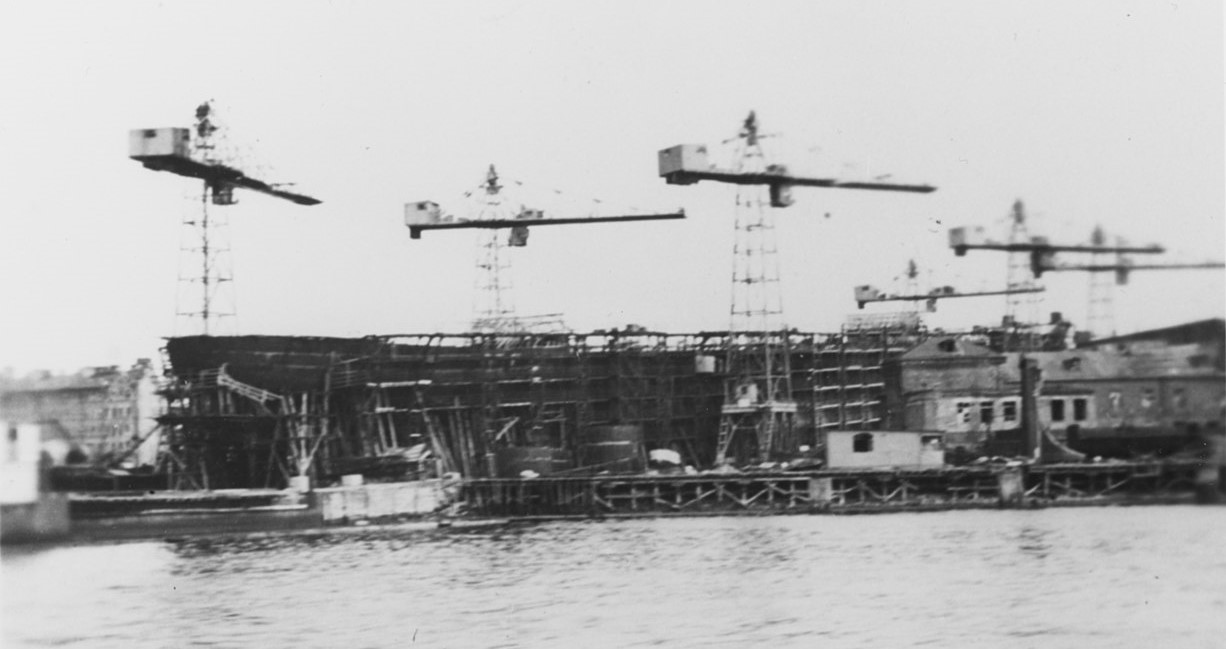

The biggest was that they clearly used the model of the USS Kidd, a Fletcher preserved in Baton Rouge, where they did a lot of filming. But the movie is set in February 1942, and the first unit of that type didn't commission until June. That wouldn't be the end of the world, but there's a lot of equipment (the Mk 12/22 radar and quad 40mms) that wasn't developed or fitted until much later in the war. There's also some internal stuff that didn't exist at the time, such as the CIC and PPI for the radar. At least the sonar had an A-scope. The whole thing felt a bit off for me, although most people wouldn't notice.

But that aside, it worked about as well as it could have. I don't know how it would have worked for someone who hadn't read The Good Shepard, but we saw as much of Krause the conflicted man as you could reasonably get in a very different medium, along with a decent portrayal of the tension of fighting submarines. My only issue with the last part was the Germans tapping into the TBS (as far as I know, that never actually happened) but I did really like the response of calmly switching channels. On the whole, it worked, but this probably wasn't the best story to make a movie out of, because of how much the book was concerned with Krause as a character, which doesn't make the transition to the screen that well. Still worth a watch if you get a chance, although I really wish I could say to go see it in theaters.

Thinking it over later, I realized I'd missed one of the things that they'd gotten very right, which was that it didn't feel off at all. Most of the time, portrayal of military life is at least a little bit off because it's hard to accurately show the flavor of a military organization if you're not really familiar with it. Hanks (who wrote the screenplay) is familiar enough to pull it off so well that I didn't even notice. So that's a major mark in the movie's favor.

Recent Comments