The basic principle behind radar is fairly simple. The radar sends out a pulse of radio waves, some of which bounce off of whatever happens to be in their path. These reflections are picked up by the radar and used to build a picture of whatever happens to be out there. But this simplicity masks deep complexity, as various portions of this are implemented in different ways, and even from the earliest days of radar at sea, ships carried multiple sets optimized for different missions.1

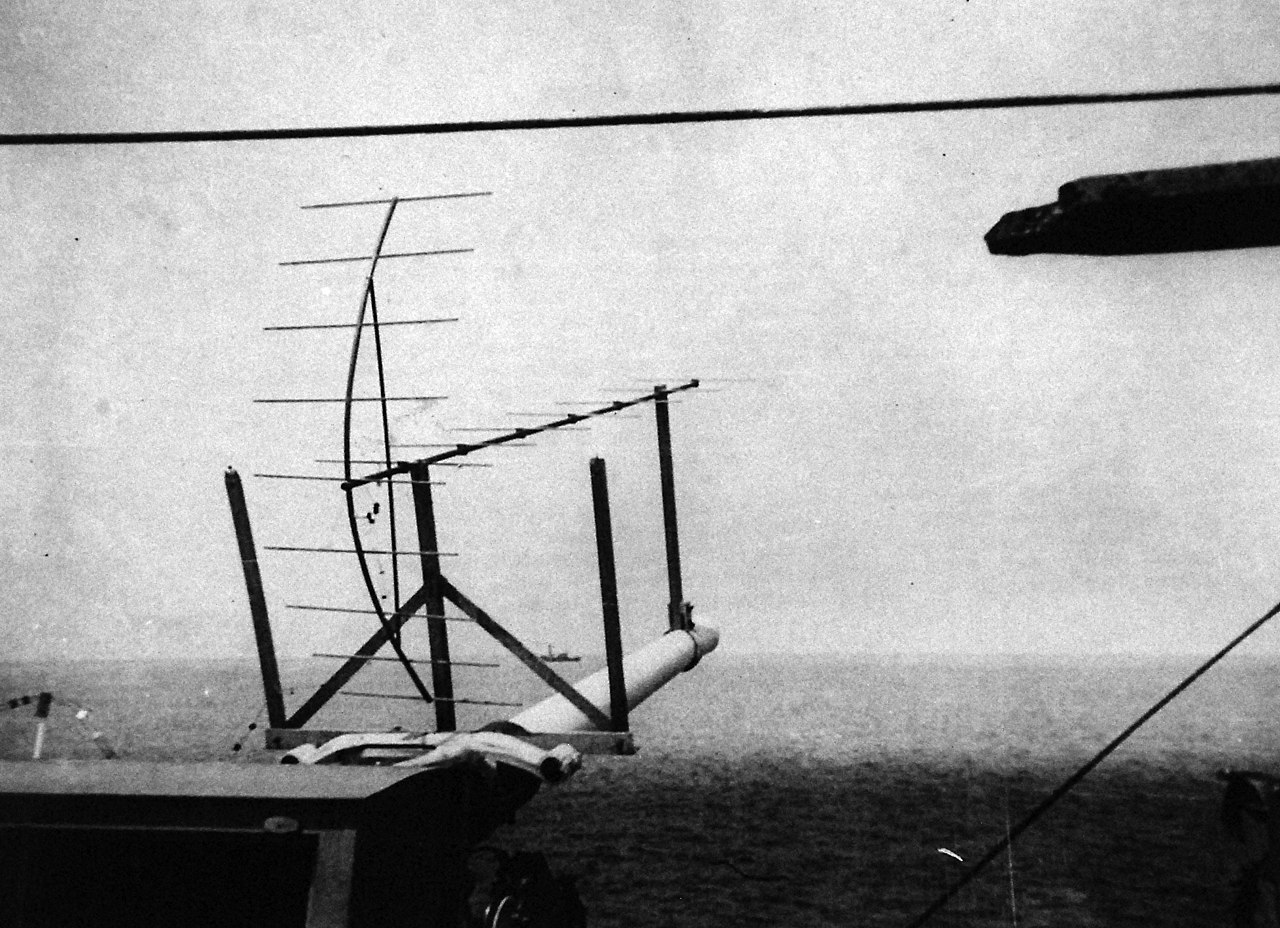

The first USN at-sea radar test aboard the USS Leary, 1937

The first radars, as developed in the late 1930s, were extremely crude. A transmitter would send out a short pulse through an antenna shaped to focus the signal in a particular direction, and then switch over to listening for the echos through the same antenna.2 The returned signal would be displayed using a device known as an A-scope, a special cathode ray tube. Essentially, the A-scope would draw a horizontal line for each pulse, deflected up (or down) depending on the received signal strength at a given range as measured by the round trip speed-of-light delay. An object reflecting the beam would appear as a spike or trough on the line, depending on how the A-scope was set up. This gave the operator precise knowledge of ranges, a vast improvement over previous methods, but only in the direction the antenna was pointing. Checking different bearings required rotating the antenna, often manually, and left the operator with the job of keeping track of what was going on around him. This didn't make it impossible to use radar data to build a picture, as the British did with the Chain Home radar feeding information to the Dowding system, but this took lots of manpower and organization. Read more...

Recent Comments